Managing Warehouse Labor to Reduce Expenses

As rising warehouse labor costs eat into their logistics budgets, many manufacturers seek ways to improve warehouse productivity and reduce facility headcount. But meeting these goals is not easy, given the sheer number of technological tools and strategies available to managers.

A useful starting point is to ascertain your current level of technological sophistication. Are your warehouse operations still grounded in manual processes or run by high-tech systems that maintain downward pressure on labor costs?

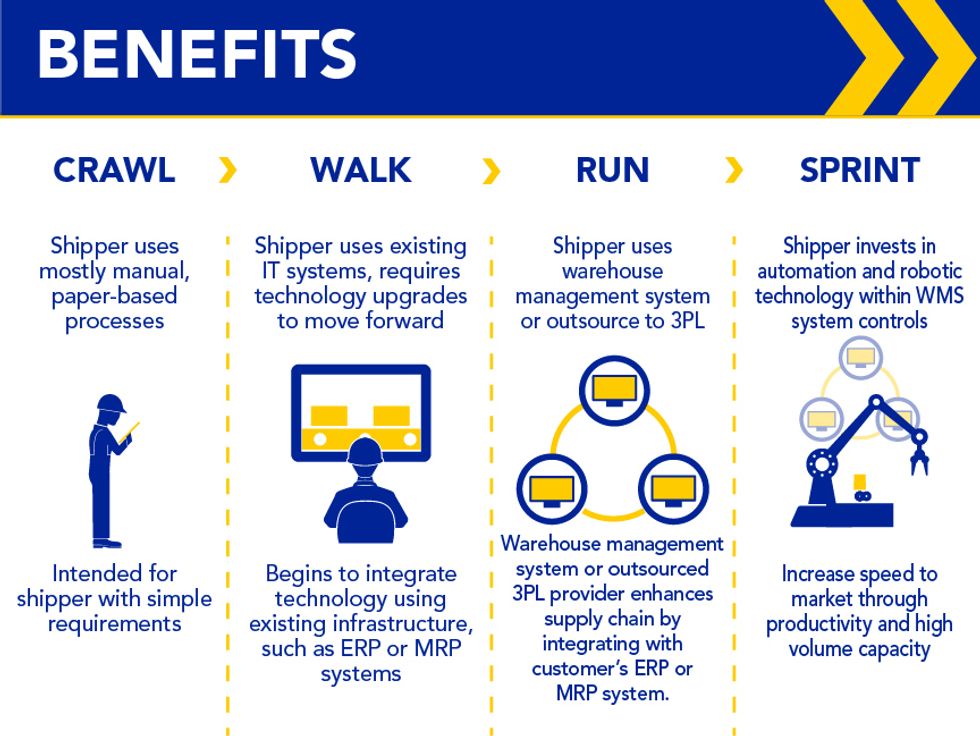

To help manufacturers make this call, Penske Logistics has created a four-stage guide to warehouse automation. Manufacturers can use the guide to help them develop a strategy for automating warehouses that is in line with their budgetary and business goals.

Personnel Premium

The cost of labor can account for up to 65% of total warehouse fulfillment costs (excluding trucking), depending on how a facility is owned and managed. It represents the most significant slice of a manufacturer’s warehousing budget.

And that slice has increased in size over recent years. Worker-related costs have soared in response to increased economic activity and a tight labor market. The growth in e-commerce volumes, as well as the number of SKUs, has driven up demand for storage space — hence, demand for people needed to run facilities.

But hiring enough workers is not the only problem; retaining them can also be a headache. In the 2018 Warehouse and Distribution Center (DC) Operations Survey published by Logistics Management magazine, the “labor crunch” is described as the number one issue. Fifty-five percent of respondents — up six percent compared to the previous year — cited an inability to attract and retain a qualified hourly workforce as the leading industry issue.

“Labor shortages and high turnover make it harder for warehouse managers hoping to control costs and boost productivity by improving workforce capabilities through training programs. As a result, more companies are seeking technological solutions to cost and productivity challenges,” says the 2018 State of Logistics Report, co-sponsored by Penske Logistics.

Making the Leap

While technology is key, choosing the most effective mix of solutions can be a daunting challenge, especially for manufacturers that lack relevant expertise.

Penske’s four-stage guide to warehouse automation can get you started.

Penske’s four-stage guide to warehouse automation comprises four evolutionary stages: Crawl, Walk, Run and Sprint.

As can be seen in Figure 1, the guide comprises four evolutionary stages: Crawl, Walk, Run and Sprint. Crawl, the most basic level, denotes largely manual, paper-based warehouse management practices and systems that most manufacturers have left behind. At the opposite end of the scale are members of the Sprint group: companies that have invested heavily in high-end solutions such as advanced picking robots, automated guided vehicles and extremely sophisticated storage systems.

For many industrial manufacturers, the middle two evolutionary steps are of the most interest. Companies in the Walk phase have introduced some automation using their existing IT resources, typically an Enterprise Resource Management system (ERP). The problem is that ERPs are not designed to handle the complex processes that drive modern warehouses.

Importantly, while Walk is a step up from Crawl, it does not harness the power of the advanced warehouse management systems (WMS) that characterize the Run phase. As a result, a critically important task when migrating from Walk to Run is mapping standard ERP-based interfaces such as one that confirms orders have been received to a WMS (see the 10 Walk interfaces depicted in Figure 1). The migration can take months and requires extensive knowledge of warehouse solutions — which is why manufacturers often turn to third-party logistics providers to help them make the jump.

“You can then optimize warehousing operations, for example, by implementing systems that put inventory in bulk locations or active locations to pick orders at ground level to increase pick speed,” says Don Klug, vice president of distribution center management, Penske Logistics. Introducing wearable scanners is another way to drive up pick speed. Goods flows can be accelerated by configuring operations to handle inventory items that are slow, intermediate or fast movers.

The possibilities for improving warehouse productivity and reducing head count are limited only by the scope of the WMS and the skills of the logistics management team using it.

Having identified potential solutions, warehousing professionals can apply technology to select the best options. “For example, Penske has engineering tools that can show customers the ROI of different solutions; if you spend “X” amount of capital, you will capture “Y” amount of productivity,” says Klug.

Increased Use of 3PLs

In a volatile economic climate, it is difficult to project with certainty how warehouse labor cost pressures will trend over the next few years. But even if there is some retrenchment, technology will be at the heart of strategies for raising the efficiency of warehousing.

3PLs will continue to play a central role. In the 2020 Third-Party Logistics Study, co-sponsored by Penske Logistics, 73 percent of the shippers surveyed outsourced warehousing to third-party logistics providers, a four percent increase over the previous year.

The research “highlights once again how important it is for 3PLs to provide a range of IT-based services to help create value for their shipper customers,” the study says. And warehouse/distribution center management is one of the most frequently cited technologies in the study. In the 2020 study, 63% of shippers said they need warehouse/distribution center management IT capabilities from their 3PL providers.

Additionally, the study noted that optimization is occurring within the warehouse, which plays a crucial role in speeding deliveries, managing inventories and cutting costs. “Logistics providers can track the flow of inventory through and around the warehouse, monitor product velocity, and provide advanced notice of arrivals, which drive reduced dwell time and engine idling and increased efficiency,” the study says. “Data on incoming and outbound loads can be transmitted electronically between supply chain partners to reduce downtime.”